For someone steeped in an idealistic or classical economics view of the world, the question of what drives investment actions is easy – it should be logic, rationality and facts.

In fact, even reputed investment product providers appear to adhere to this view, going by a quick drive through of their websites to non-clients.

Could they be wrong?

There are a lot of choices and selections that a prospective customer needs to make before ever seeing a reward or payoff in terms of a tangible result, even if it is as small as opening an account. In addition, the process is fraught with friction and barriers to progress.

There are many studies on how people in the real world make these choices (with behavioral finance literature being my favorite hunting ground to find these).

But I was interested in understanding at a very visceral level how this process works for women who had an admitted “strong” desire to “learn more about investing” but had not done so in any meaningful manner for a variety of reasons (more on these later).

With this end in mind, I undertook a completely anecdotal and unscientific survey of a handful of my female compatriots to get a qualitative understanding of their experiences with investing.

I supplemented this with an in-depth review of customer reviews from a few books that target women interested in investing (I’ve written more about this exercise here).

Collecting the data

To collect the data, I talked to my cohorts, and asked them questions about:

- Their level of desire to invest

- Their knowledge and level of confidence in investing

- Actions they took to invest

- Current status

- Barriers to and drivers of their investing actions

Additionally, I also reviewed key comments from user reviews on Amazon as referenced here, to identify themes relating to the topics above.

The results:

- All the women expressed a strong desire to do better in investing

- Across the board they also expressed a lack of confidence in their abilities

- An intense shortage of time and bandwidth to do anything further on their investing activities further challenged their ability to make progress they desired

These themes were reflected in the book reviews as well, although confusion and intimidation came through more clearly in the Amazon comments. (For the Amazon reviews, I only focused on women who indicated a strong interest in investing as part of their comments).

The drivers of investment advice and behavior:

There are four key drivers that can drive investing behavior and sourcing of investing information, guidance and advice.

Trust and understanding:

Their trust in the source, coupled with the source’s understanding of their particular situation, appears to be the tie-breaker in their decision to seek and heed investment advice. This is puzzling because they admitted that the source they trusted (typically a male in the family), was probably not the best-qualified.

Yet, this choice was preferred even with known concerns on competence, to going to a more competent source but who was perceived to be “sales-y”. This begs the question of what drives trust. In short, it is either someone whose trust they consider proven, or a referral from such a person.

A second related thread under trust is the extent to which the source understands the specifics of their unique situation, concerns, their life context. This qualitative understanding appears to be a key driver. (Later in this blog, I will be writing about the results of another , vastly more scientific study on what women want from their financial providers, but here is the spoiler – they don’t contradict anything here).

When women feel that the source doesn’t understand them as people, the chances that they will pick that source drop very low.

Low behavioral friction (“Make it easy”)

Next to trust, the second biggest driver appears to be how easy it is to do the activities that constitute the investment process. The harder this process, the less likely that these women will go all the way to completion. Because of the heavy burdens most women face on their time, bandwidth and resources, it’s hardly surprising that behavioral frictions are likely to have a magnified effect on their interest in proceeding.

As a small example, even the need to provide one small piece of extra information that is not readily at hand is perceived very negatively.

High behavioral payoffs (“Make it fun”)

A third factor is the emotional payoffs that come from going to the preferred source. It’s interesting to note that for people who place their faith in popular finance gurus and their methodologies (with no comments on their competence), three things really seem to matter greatly:

- the rewards of social proof of the thousands of others also following the method,

- the removal or at least reduction of choice (and therefore the hard work of evaluating them),

- the need to feel safer and more settled (whether justified or not)

Simply said, the need for emotional assurance seem to outweigh every other logical factor.

Objective results:

Objective results are a tough area to evaluate. This is partly because there is no simple and universally appealing benchmark (other than tracking to a broad index).

Even having to pick an objective standard to evaluate to, induces anxiety and uncertainty, with the result that this factor was rarely or peripherally mentioned, other than in a very general way (for example, “Of course, the investments have to do well”).

The one consistent yardstick that came up in virtually every conversation I had was “I don’t want to lose money”.

This brings up the interesting challenge of how women can expect to appreciate their wealth over the long-term without taking equity risk, but that’s a topic for an entire book, and will not be addressed here.

Suffice it to say that as long as there was some assurance that there would not be large losses, or any losses at all, most other criteria (excepting trust) trumped this one in their minds.

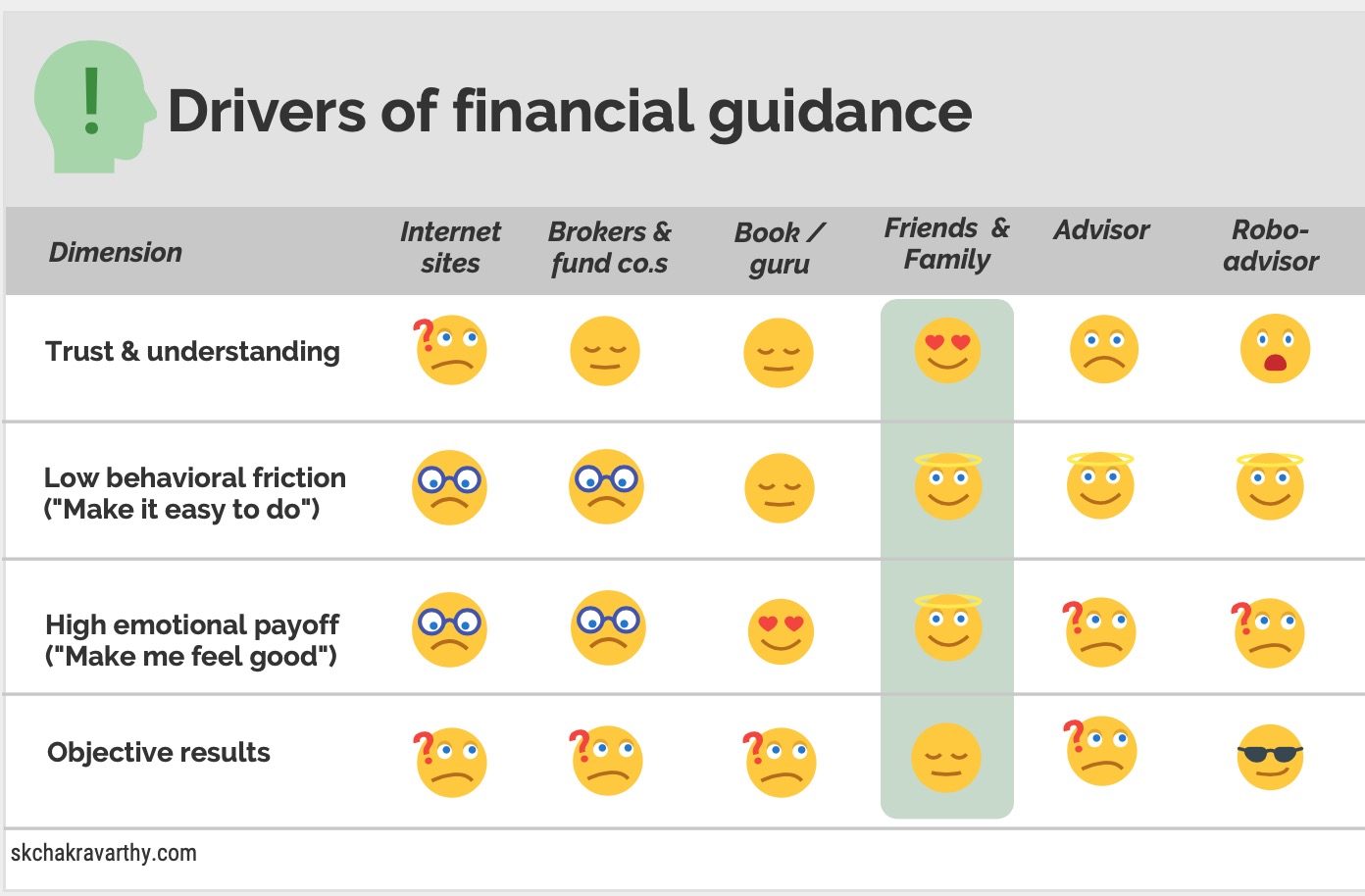

So where does this put the various sources of investing advice? And more importantly, what are the implications for providers who want to attract a greater share of women’s investing dollars?

Here is a simple infographic that summarizes what I discovered:

The bottom line?

Trust and understanding seem to beat out almost every other factor in this small survey.

Action implications:

The main lessons here are applicable to larger investment product providers, advisors and especially to robo-advisors:

- Demonstrate understanding of the personal factors of each individual: This does not need to translate into a human-to-human service model, although that certainly helps. Even having the capability to recognize and “play back” to the individual any specific aspects of their lives, preferences or contexts is likely to have a disproportionate impact on women’s willingness to consider the provider favorably

- Remove friction at every step in the process: The investment process is overloaded with difficult and uncomfortable steps and decisions. While many of these are necessary to meet regulatory requirements and to protect investors’ own interests, the industry has done too little to walk in the shoes of their customers to truly understand what a cognitive and task-based burden their processes place on women who want to do business with them. Even simple steps like providing a roadmap of the process in advance of entering it, or a list of documents they need, will vastly improve the user experience and increase adherence and conversion

- Increase behavioral rewards and payoffs: Small emotionally and behaviorally meaningful rewards are even more important in an abstract and intangible domain like investing. We saw in an earlier post how even creating something as simple as a punch card to track deposits into a savings account can vastly increase adherence. Similar tangible rewards, markers and other rewards that are meaningful and salient to the “lizard brain” that’s driving the bus in all of us are extremely important when it comes to driving and promoting investment behavior.

Taking this simpler lens to evaluate the existing value proposition is likely to yield large benefits for small changes